“The queen is dead?” a preschool administrator in suburban Paris asked Matthieu Bize, a wasp controller who had come to rid the schoolyard of Asian hornets.

By Chantel Tattoli

Oct. 28, 2020

On the ground, a nest was in tatters. Twenty minutes earlier, it had been high up in an ivy-choked tree, where it looked like a jumbo gray-brown balloon. Mr. Bize, 32, had sent a telescopic pole through the canopy, injected a paralyzing white powder into the hornets’ home, and knocked it down. The colony’s larvae, future queens among them, were strewn about. “Nearly finished here,” he said.

In English, the Bize family name is pronounced “bees”; in French, it is “bise” (short for kisses). Dozens of times a day, when Mr. Bize answers his cellphone — “C’est Monsieur Bize” — this gentle phrasing sweetens an otherwise sting-y situation.

For Mr. Bize doesn’t hunt just any pest. One-third of the nests to which he responds belong to a species of dreaded “murder hornet,” a type of wasp that beheads and feeds to its larvae an insect that is very important to, and symbolic of, France: the honeybee.

Beyond the fact that Napoleon chose the honeybee for his logo in the early 19th century (the emperor favored the insect for its tenacity), France is the European Union’s largest agricultural producer, and generally known for pollinator-friendly policies. It is also one of Europe’s major honey trade hubs.

The Asian hornet first appeared in southwest France in 2004, possibly having traveled from Southeast Asia as a stowaway in a pottery shipment that docked in Bordeaux. “I actually did not imagine this species would reach the capital,” said Adrien Perrard, 33, a researcher of bee biodiversity at Sorbonne University. But in 2015, it did.

France’s honey production was at a 20-year low, and Paris had become a newfound oasis for honeybees and their keepers. Reports of hives bedeviled by the arrivistes mounted. Mr. Bize was then a sommelier, but as the honeybee versus hornet crisis of Paris intensified, his brother, a fireman named Gregory, roped him into wasp work.

“There was no training,” said Gregory, 38, wincing at the memory of learning on the fly. He’d been fending off hornets as a firefighter in Paris; when his department punted the wasp problem to private pest technicians, a side business was hatched.

Thus, the brothers Bize won the municipal contract for wasp control in Paris. In two vans, they zigzagged to calls to nix nests citywide, one working the Left Bank while the other worked the Right Bank, as Gregory’s wife, Léa, acted as dispatcher.

Spring. Summer. Fall. The city paid handsomely, but the caseload was gruesome. Now, the Bize brothers live and work in the suburbs just outside Le Périphérique. They destroyed some 300 Asian hornet nests in 2019. “Last year was not that bad — this year is heavy,” Matthieu Bize said. “Beaucoup d’activité!”

Wasps’ numbers are at their max in late summer, and because of a mild spring, the city was lousy with both native wasps and the Asian hornets this year. They tortured the bakers’ brioches. They danced on the fishmongers’ squid. They sailed into fifth-floor flats to drink from the juice cups of babies and even appeared on buildings as human-size graffiti.

“It’s a very good year for this hornet,” said Quentin Rome, an expert on the Asian hornet at the French National Museum of Natural History. (Vespa velutina, the wasp in question,is often confused with Vespa mandarinia, the giant “murder hornet” that made its way to Washington State, but that species is not in France.) “They are desperate to get other insects to feed” to their larvae, Mr. Rome, 40, said. “The hornets are extra-aggressive with the honeybees in the autumn.”

Hornets eat a variety of insects, but beehives are easy marks. A hornet “hawks” the hive, Mr. Perrard explained, hovering around the entrance until it catches a honeybee and carries the sweet petite away.

“It really stresses the bees,” said Lionel Potron, the founder of Apis Civi, the city’s only maison de miel(honey house)with a beekeeping school. “They know the hornets are there and won’t leave to forage. And if they don’t forage, they starve during winter.”

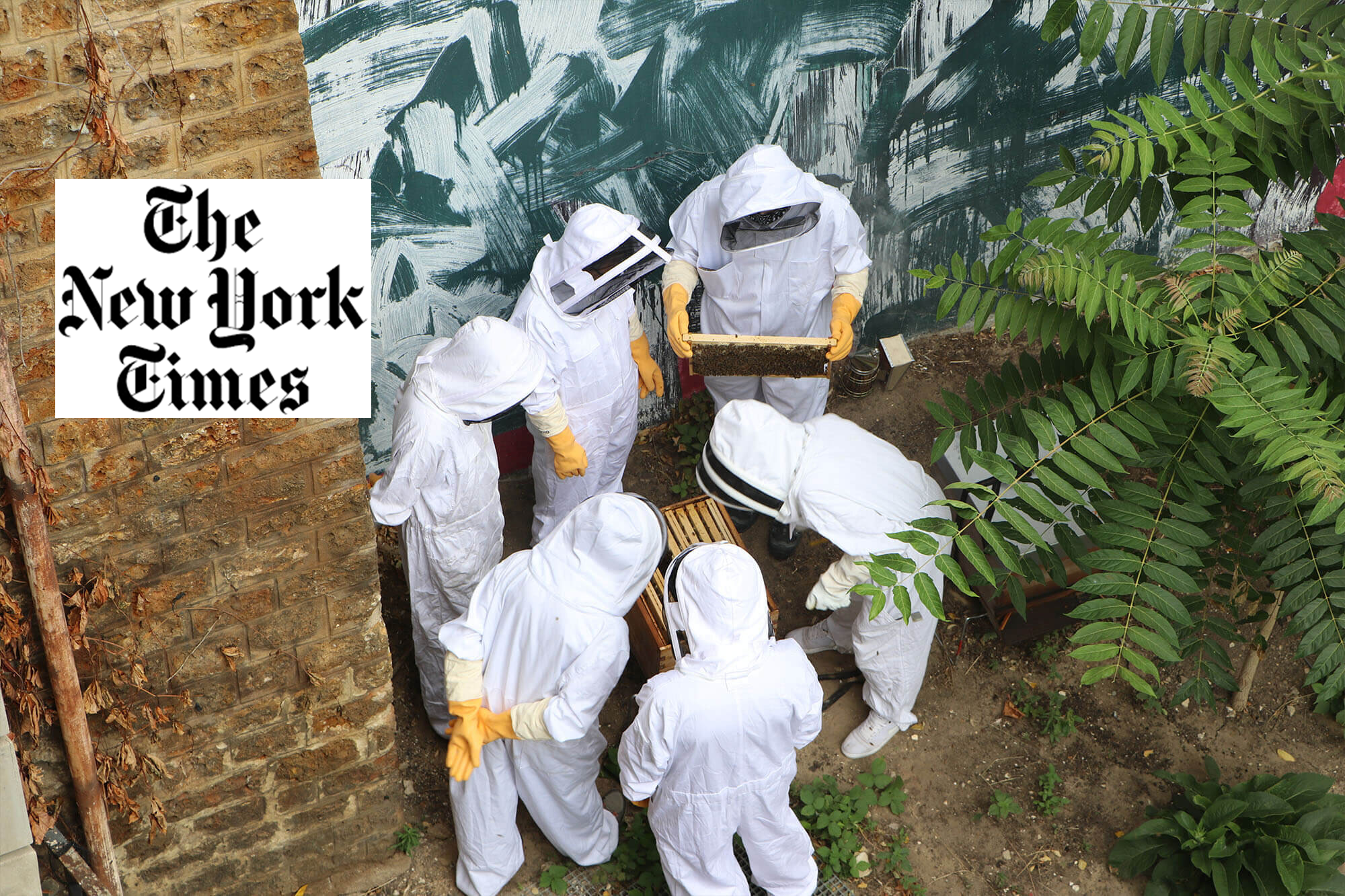

It was the end of summer and Mr. Potron was supervising a class at an apiary on the edge of the Bois de Boulogne, one of two forests in Paris. Nearby, a beekeeper trainee wielded a bug zapper shaped like a tennis racket. Mr. Potron and his students had intercepted dozens of bee-hawking Asian hornets in the past hour.

Apis Civi, founded in 2016, has 250 beehives in neighborhoods across inner Paris, including Champs-Élysées, Montmartre and the Marais, and another 150 hives in Greater Paris. Honey can be reserved from hives in the neighborhood of a customer’s choice; a deluxe version is offered with gold flakes. (It sells mostly to clients in the Emirates.)

“Depending on the location, there is variance in the taste,” Mr. Potron, 41, said. His metropolitan bees have some 2,000 flowering plants at their disposal. The honey owes much of its flavor profile to the horse-chestnut, black locust and linden trees.

France forbade synthetic pesticides in public spaces in 2017, but Paris had done so nearly a decade earlier. Now, “Parisian honey also tests very clean,” Mr. Potron said. “I tell my students that we could triple our supply and it would still sell out.”

Mr. Potron plans to expand Apis Civi to cities in other countries, hoping to begin next year with Monaco. “Urban beekeeping is exploding,” Mr. Perrard said. “It has exploded in Paris.”

That turns out to be its own kind of sticky situation.

Like the hornets, domesticated honeybees are also “invasive,” said one of Mr. Perrard’s colleagues, the local pollination ecologist Isabelle Dajoz. “This urban beekeeping trend must stop.”

“In 2020, there are more than 2,000 hives downtown, that we know of,” Ms. Dajoz, 57, said. “It works out to 20 hives per square kilometer — 10 times higher than the national average.”

And though honeybees are managed bees, she said, “they are competing with the species of wild native bee — like the bumblebee — and with butterflies, for flower resources.” Most pollination is performed by those wild pollinators, especially for wild plant species, and even in urban habitats, Ms. Dajoz added. If there are too many honeybees, the wild pollinators are pushed out of the landscape.

After Ms. Dajoz’s findings, the mayor’s office issued a moratorium on new hives in public spaces last fall. In the entangled theater that is an ecosystem, the honeybee, a victim of hornets, has become an accidental victimizer too.